CDC Releases Interim Flu Vaccine Effectiveness Report

February 26, 2020 10:01 am

Chris Crawford – According to a

Feb. 21 CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report,(www.cdc.gov)the current influenza vaccine has been 45% effective overall against 2019-2020 seasonal influenza A and B viruses.

Specifically, the flu vaccine has been 50% effective against influenza B/Victoria viruses and 37% effective against influenza A(H1N1)pdm09.

https://www.aafp.org/news/health-of-the-public/20200226interimfluve.html

P.S. The report does not answer the second part of your question.

Thank you Nomad. As you might well have deduced, I'm interested in the media reports which state that until a vaccine is made available for Covid-19, there can be no relaxation in any of the restrictions regarding social distancing, resumption of football, F1 and so on.

It occurs to me that the availability of flu vaccines has seemingly failed to limit the numbers of infections and deaths in the many years that they have been available, and I wonder therefore if and when a vaccine against Covid-19 is made available, it will do no more than act in a similar way to appeal to those seeking a "miracle cure" and relegate the condition to one that is no more newsworthy than flu.

The following, taken from

www.reliasmedia.com/articles/145907-flu-season-charts-an-unusual-course-beginning-with-a-predominant-b-victoria-strain quotes from CDC reports on flu:

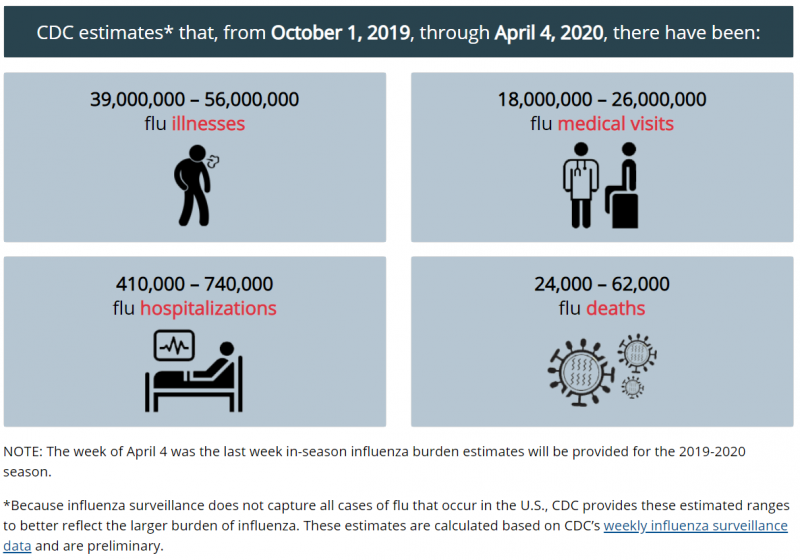

"Overall, the CDC reported there have been at least 29 million flu illnesses, 280,000 hospitalizations, and 16,000 deaths related to the flu this season. As of mid-February, epidemiologists observed evidence of influenza activity had only slightly decreased from previous weeks.

In a bit of good news, the first estimates on flu vaccine effectiveness, unveiled in late February, show the current formula is reducing doctor visits for flu by about 45% overall and 55% in children. Further, data show the vaccine is effective against both predominant circulating virus strains."

The relevance of the remainder is questionable regarding Covid-19, but some may find it interesting anyway:

"Clinicians can expect to see many typical manifestations of uncomplicated flu virus when patients present, explained

Angela Campbell, MD, MPH, a medical officer in the CDC’s influenza division who also spoke during the Jan. 28 COCA call. “This can range from asymptomatic infection to a more typical upper respiratory tract illness, typically consisting of an abrupt onset of fever and cough with other symptoms that may include chills, muscle aches, fatigue, headache, sore throat, and runny nose,” she explained. “A runny nose and nasal congestion symptoms also occur with more common cold viruses as well, but they may occur in young children with the flu. GI symptoms such as abdominal pain, vomiting, and diarrhea tend to be more common in children.”

However, Campbell stressed young infants may not exhibit any respiratory symptoms at all, and may present with fever alone, often accompanied by irritability. She also noted elderly patients and those who are immune-suppressed may present with atypical symptoms and may not even report with any fever.

Clinicians also should be aware of the complications that can go along with flu. For instance, Campbell noted otitis media can develop in up to 40% of children younger than age 3 years who have the flu. It also can exacerbate chronic underlying conditions such as asthma. “Other common causes of hospitalization with flu include dehydration and pneumonia, and pneumonia can be primary viral pneumonia or secondary bacterial pneumonia,” Campbell explained.

Campbell added flu can cause other respiratory syndromes and extrapulmonary complications such as renal failure, myocarditis, pericarditis, myositis, and extreme rhabdomyolysis. “Flu is also known to cause encephalopathy and encephalitis, particularly in children, as well as sepsis and multiorgan failure,” she shared. “In fact, in a relatively recent review of death reports of children who died with flu, sepsis was actually found to be listed as a complication in up to 30% of those reports.”

Bacterial co-infections can cause severe disease when present with flu, Campbell said. She noted the most common bacteria involved in these cases include

Streptococcus pneumoniae,

Staphylococcus aureus, and group A

streptococcus.

When should clinicians order tests for the flu? Campbell noted such testing is in order when the results are likely to influence clinical management. For example, if the results may decrease unnecessary lab testing for other etiologies or the unnecessary use of antibiotics, testing is advised. Further, if the results might facilitate implementation of infection prevention and control measures, increase the appropriate use of influenza antiviral medicines, and potentially shorten length of stay, flu testing is indicated.

“Another reason for testing is if it will influence a public health response. It can be very useful for outbreak identification and intervention,” Campbell said. “One of the most common situations where this is the case is in long-term care facilities or nursing home outbreaks.”

The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) produced an algorithm that can be used to help clinicians determine whether to order flu testing. This graph, along with additional guidance, is included online at:

http://bit.ly/2HZZz5m.

“If a patient with suspected flu is being admitted to the hospital, testing is actually recommended both by IDSA and by CDC, along with empiric antiviral treatment while results are pending,” Campbell said. “If [the patient] is not being admitted, but if results will influence clinical management, the same recommendation applies.” In cases where flu testing results will not influence whether empiric treatment can be initiated based on a clinical diagnosis, then there probably is no need for it, Campbell added. However, she also noted empiric treatment is recommended in cases in which the patient is at high risk or presents with a progressive disease.

When considering antiviral treatment for flu, the focus of CDC’s treatment guidance is on the prevention of severe outcomes, Campbell noted. Consequently, this guidance is particularly aimed at patients with severe disease and those at the highest risk for severe disease. “Clinical trials and observation data show that early antiviral treatment can shorten the duration of fever and flu systems,” she said.

In particular, Campbell observed early treatment reduces the risk of otitis media in children and lower respiratory tract complications that require antibiotics and hospital admission in adults. Further, she noted both observational studies and meta-analyses have shown early antiviral treatment reduces the risk of hospitalization in high-risk children and adults.

Regarding oseltamivir, one antiviral medication, studies have revealed early treatment reduces the likelihood of death in hospitalized adult patients, and the drug has been shown to shorten the duration of hospitalization in both adults and children, Campbell said.

Considering the demonstrated benefits, the CDC recommends antiviral treatment as early as possible for any patient with suspected or confirmed influenza and severe, complicated, or progressive illness, or who is at high risk for influenza complications. This includes children younger than age 2 years, adults age 65 years and older, pregnant and postpartum women, American Indians and Alaska natives, children on long-term aspirin therapy, people with underlying medical conditions, and residents of nursing homes and chronic care facilities. “Clinical benefit is absolutely greatest when antiviral treatment is initiated as close to illness onset as possible. Treatment really shouldn’t be delayed while testing results are pending,” Campbell stressed.

However, she noted antiviral treatment initiated after 48 hours can still be beneficial in some patients. “There have been observational studies in hospitalized patients that suggest treatment might be beneficial even when initiated four or five days after symptom onset. Similarly, there have been observational data in pregnant women that have shown treatment to provide benefit when started three to four days after symptom onset,” Campbell reported. “But by and large, the earlier [treatment commences], the better. Even within the first 12 hours is better than within 24 or 48 hours.” Beyond the high-risk groups, antiviral treatment also can be considered for any previously healthy patients with suspected or confirmed flu. This determination can be made on the basis of clinical judgment if treatment can begin within 48 hours of illness onset, Campbell said.

Part 2 follows